Tradition? Part 2...

(This is the second part of a three part article. Scroll down to find part 1)

I came away from the Totnes school feeling a bit smug about my newly acquired skills, (now I cringe at the memory of my smugness), and I opened up my business making guitars the way I learned in England. My dad would come and hang out at my shop to check out what I was up to, and, looking back, I could tell he was patiently putting up with my "preciousness". He came from the tradition of making jigs and fixtures in order to do complex woodwork using power tools. Every so often, while watching me do something such as leveling a back plate with a jointer plane, he would politely ask why I couldn't figure out a way to do this more quickly. I remember feeling a little affronted at such a suggestion (gag me with a spoon) and I would tell him there were good reasons for doing it the way I was doing it.

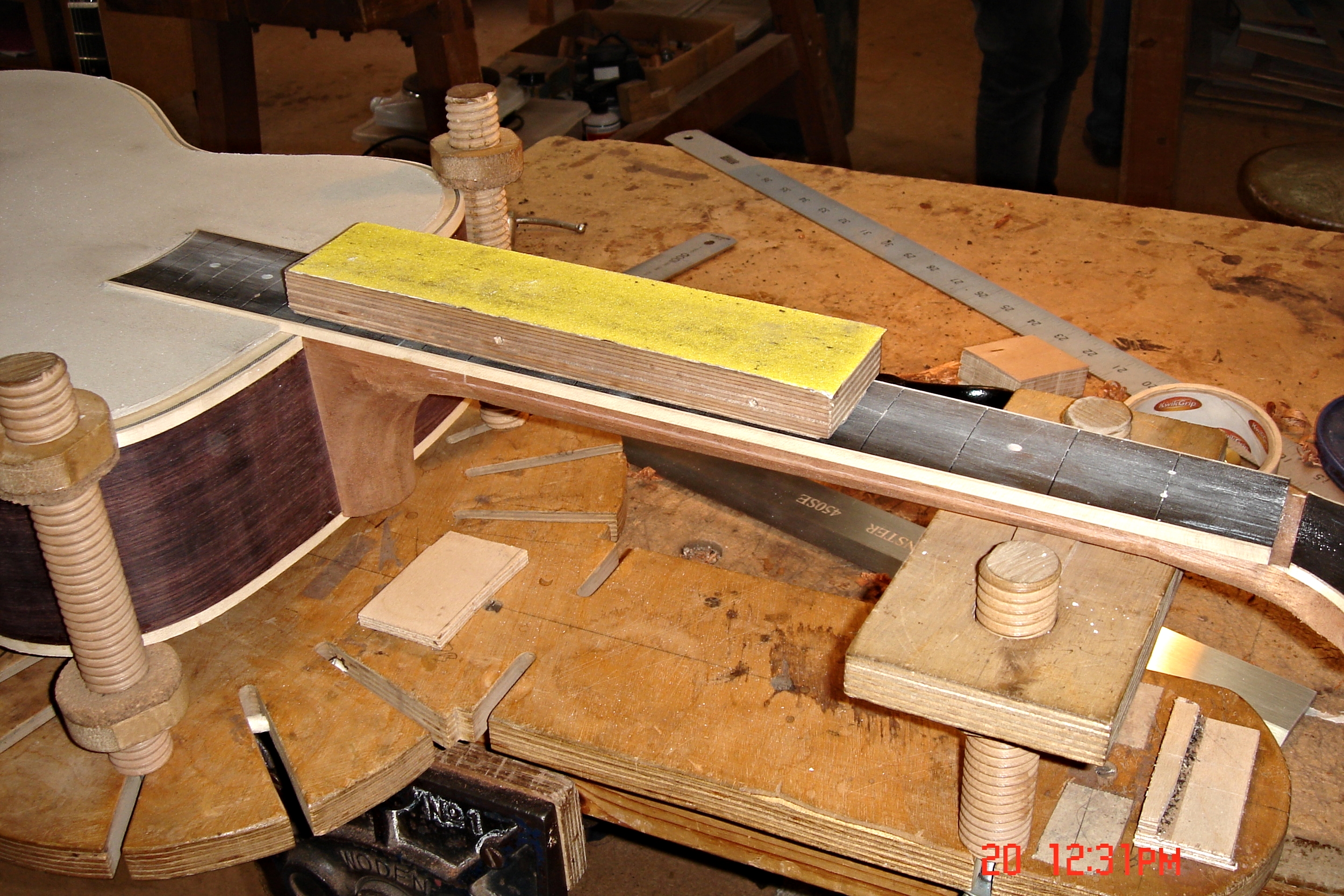

Thicknessing a Waterfall Bubinga back plate

Well, it didn't take too long before I found myself wondering the same thing. It was taking me a long time to complete a guitar and I realized that I was still very much a beginner with the traditional use of hand tools. I began to search the internet for how other guitar makers executed certain tasks; arching the braces, in particular, continued to be a source of frustration to me. Arching a brace is the process of putting a radius on the side of the brace that is glued to the top or back plate. Most "flat-top" guitars have a slight radius to the top and a more pronounced radius to the back, which, among other things, adds strength. At the Totnes school, I learned how to arch a brace using a mathematic calculation and a hand plane. It worked, but every brace was unique, so the process of shaping all the braces in a guitar was very time consuming. I scoured the internet for ideas and soon I came upon a way to make braces in a fraction of the time it was taking me. In a small way, it was kind of like losing my faith. Instead of losing my faith in a religion, it was the tradition that I had learned that I was disavowing. There are some remarkable similarities here, but that's a whole different ball of wax.

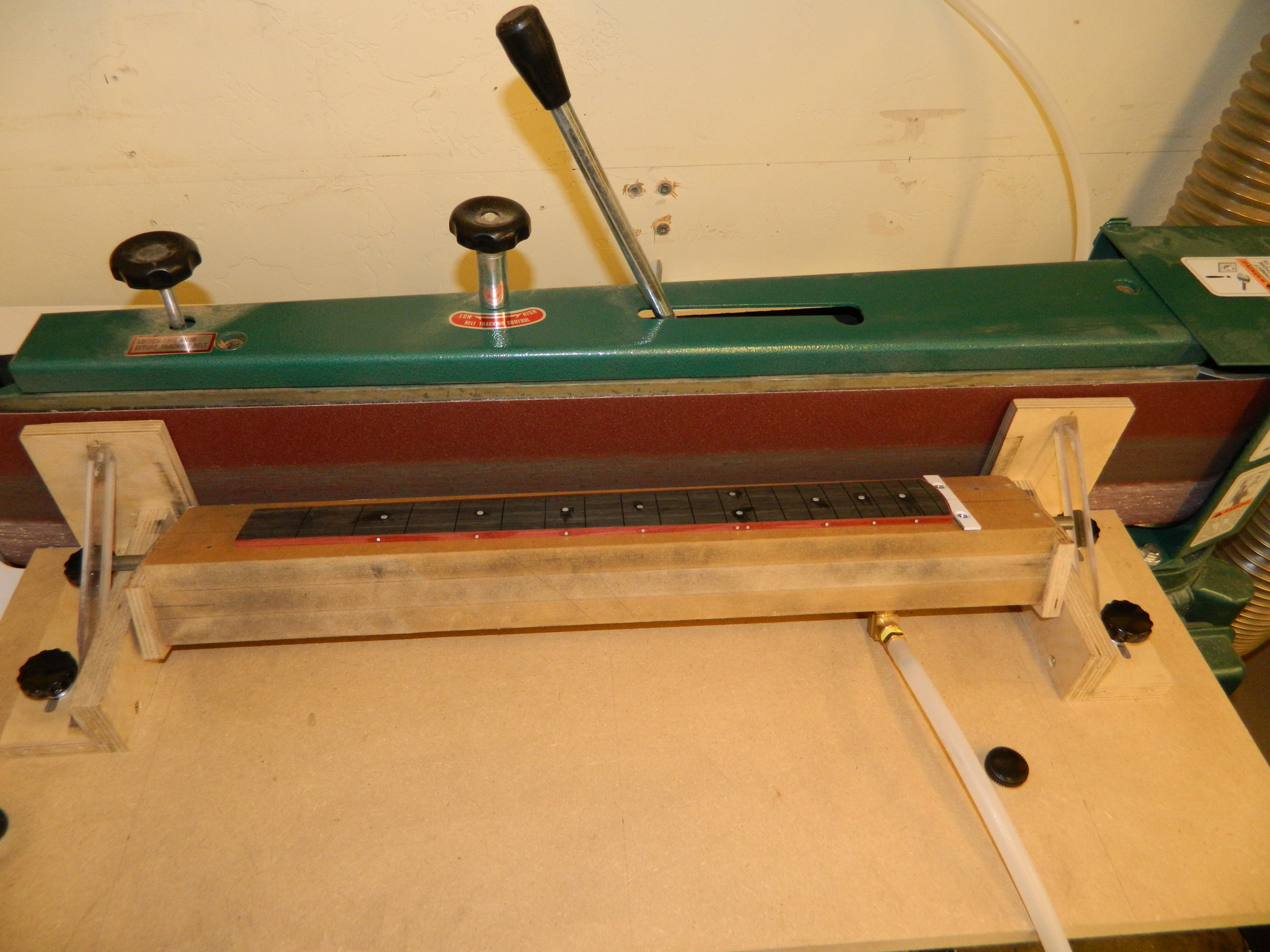

Arching a Spanish Cedar back brace with a Jack Plane

Two back braces arched

At the time, I was offering two models of guitars. So, I realized that if I could make master set of braces for each model, and then duplicate the master set, I would be saving literally days and days of labor. I ended up making a simple pattern jig that held an unshaped brace over a brace-specific radius, and then used a pattern router bit to shave the brace to the correct radius. As with any jig, there were kinks that had to be worked out or around, but I eventually nailed it down and ended up making enough braces for around ten guitars in a couple of days. That was the turning point for me. After that, my mind began to fixate on ways to speed up the process of making a guitar without sacrificing quality. Coming up next, Charles Fox and The American School of Lutherie...